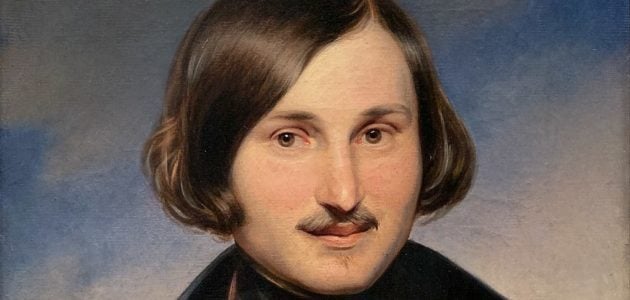

Best Plays by Nikolai Gogol

Nikolai Gogol (1809 – 1552) was a Russian playwright and author. Known primarily as a writer of novels and short stories, his contribution to theatre is nonetheless significant due to his influential satire The Government Inspector. Gogol sits at a curious juncture in history: he straddled new literary forms such as surrealism and absurdism in his work, not to mention a sombre mentality towards politics and culture that could be seen to foreshadow the impending collapse of Tsarist Russian society. However, as an artist perhaps far ahead of their own time (and focused on short fiction, which is generally regarded less in the Western Canon than novels), Gogol is often overshadowed by his direct influence Pushkin and the “great Russian authors” such as Dostoevsky and Tolstoy—both of whom would count him as an important inspiration.

Gogol’s largest bodies of work are his short stories, which were heavily influenced by his Ukranian heritage. When emerging on the literary scene with his collection Evenings On A Farm Near Dikanka in 1831, Gogol was praised as a uniquely Ukranian voice who examined the differences between Ukranian and Russian culture and life. Throughout the early years of his career, Gogol also flirted with a profession as a historian; he was thwarted, despite his enthusiasm for Ukranian history, by a lack of any formal qualifications in the academic field. With The Government Inspector (1836) Gogol first realised his full potential as an author and playwright. This influential piece of satire about provincial corruption was seen as politically dangerous theatre; ironically, it was championed into writing and production by Tsar Nicholas I. It is perhaps his best known work, and lays the foundation for the more politically-minded explorations of Russian society that would mark his later output.

The final chapters of Gogol’s life were concerned with travel, living abroad and enjoying the artistic output of foreign countries such as Italy, Germany and Switzerland. However, this period was also marked by tragedy. Gogol was severely affected by the death of his hero Pushkin, and a decline in his health saw him turn to religion with a frightening fervour. The publication of his political satire Dead Souls in 1842 was heralded as a masterpiece—and many were excited to hear that it was intended to be the first work in a loose re-imagining of Dante’s Divine Trilogy. However, plagued by illness and religious remorse, he destroyed the draft of the second part in 1852 and died in pain days later.

Forty-two years of age is hardly enough for a writer who contributed so much to so many different artistic forms. But Gogol’s influence can still be felt in works of political satire and existentialism; his love of the grotesque and surreal has permeated not only the stories we tell, but the new media that developed after his death (cinema, in particular, runs with many of Gogol’s foundational ideas around fusing an everyday object or interaction with new meaning by the lens through which it is seen). His contribution to theatre may be seen as sparse compared to others in the Western literary canon, but it is significant. Nikolai Gogol is worth reading and consideration by any serious artist.

Notable Works:

The Government Inspector (1836)

Widely regarded as one of the best satires ever written—if not plays in general. Fun-loving, fast-living civil servant Khlestakov is mistaken for a government inspector by a small Russian town’s corrupt mayor. When Khlestakov realises their mistake, he vows to squeeze them dry of every cent they have. The ‘mistaken identity’ aspect of the play is beautifully escalated, and the corruption and greed of the townsfolk make them excellent targets for Khlestakov’s shenanigans. At the climax of the play, after the civil servant has disappeared with everything the town had, the mayor famously turns to the audience in a fourth-wall break and yells “What are you laughing about? You’re laughing about yourselves!” It is the perfect, final, cynical cherry on top of this masterful piece of allegory.

The Nose (1836) [short story]

The Nose is one of Gogol’s better known short stories, and proof that his roots of surrealism and social commentary long ran through his life’s work. Ivan Yakovlevich, a government working in St. Petersburg, wakes one morning to find his nose has left his face. He travels through the city to find it—making police reports and consulting doctors—who all ridicule his situation. When he does finally track his nose down, it refuses to return: it prefers its new life of freedom all the more than living on Ivan’s face. Gogol explores themes of class and the perils of a superficial existence, infused with his trademark black humour. Although it is a short story, The Nose is regularly adapted as a stage work due to its continued relevance and engaging visual imagery.

Marriage (1842)

An indecisive man named Podkolyosin hires a matchmaker to find him a wife (such was custom in Russia at the time). When his friend Kochkaryov hears of his plans, he commits himself to helping Podkolyosin marry—knowing his friend’s tendency to stall and second-guess could cost him his happiness. Sure enough, Podkolyosin does this at the end of the play: despite Kochkaryov’s best efforts, the groom-to-be leaps out of the window of the church and escapes. This is a play that, on surface, feels more like a romantic comedy than anything else. However, the themes beneath seem to suggest a dangerous incompetence in middle class Russian society that will lead to its own inevitable destruction. In many ways, Gogol was more correct than he might have guessed.

The Overcoat (1842) [short story]

Gogol’s most famous work. A government worker in St. Petersburg is constantly mocked for his worn and shabby overcoat; he works hard to replace it, but the new overcoat is promptly stolen by ruffians. The worker complains to the local general, who mocks and provokes him. Distraught and defeated, he catches a fever and dies. However, the story then crosses into a supernatural realm: the general, feeling bad about his part in the man’s death, is confronted by the worker’s ghost—who promptly steals the general’s overcoat. Finally, another ghost—that of one of the ruffians—is seen on the streets elsewhere in the city. It appears that the worker’s misfortunes have followed him into death as well. The Overcoat is a brilliant skewering of classism and bureaucracy; much like The Nose, it has enjoyed countless adaptations to stage and screen since its inception.

Dead Souls (1842) [novel]

Gogol’s last major work is a bittersweet read: it promises so much from the writer, whose life would end a decade later in misery. The novel is concerned with the exploits of a gentleman named Chichikov, who arrives in a small town to acquire “dead souls”. These dead souls actually refer to dead peasants and serfs managed by landowners who, as “souls”, would need to pay tax and be legally registered. The protagonist plans to buy the ‘dead’ ones from their current ‘owners’, have them legally registered to him and take out a fraudulent loan against the (on paper) impressive workforce. Chichikov is revealed to be a charlatan and disappears with the money; he arrives in another part of Russia and resumes his duties, until he is eventually arrested and pardoned due to the colourful characters he meets. Gogol’s novel was episodic—which was criticised by some upon its release—but now understood to be an homage to epic poems such as Dante’s Divine Comedy and Homer’s Odyssey.

Leave a Reply