American Accent Guide

This is our American Accent Guide, by voice and dialect coach Nick Curnow. For this article, we’re going to be focusing on the General American accent, of course there are infinite regional accents in the US, but most auditions and roles simply require a General American Accent, and if you are not a native American speaker, it is important to be able to nail this accent when needed. Grab a pen and notepad, and get ready to work.

What is it?

General American, also known as Standard American, GenAm, American English, or US English, or also Detailed American English is the most commonly required, and the most commonly observed accent in US film and television today. It is also somewhat of a constructed concept. What I mean by that is that nobody grew up in Standard America. The sound we’re talking about is what is called a prestige dialect. Most countries (and most languages) have a prestige dialect which is exactly what it sounds like: the speech sounds most commonly identified with status within a given society.

Linguistically it’s not simply status but also clarity, intelligence, socioeconomic influence and general power. As listeners we absorb our unconscious biases about people based on the sounds they speak with as much as we do about the way they look or behave. Received Pronunciation (RP) is the equivalent in the UK. The French established by the Académie française is the French equivalent. In essence, it is the sound most commonly associated with clarity, eloquence and authenticity. It is also free of anything which may give a clue to the speaker’s geographical origin, ethnic background, or their socio-economic status. It is what is assumed to be “good speech.” But as I always tell my students, no sound is in and of itself “good” or “bad” – those associations come from social constructs, be they good or bad. Humans make judgements, but sounds are independent of that.

All that said, let’s talk about what makes GenAm what it is, and what it’s not. In this article I’ll be going over some basic elements and exercises. For more detailed and individual information and work you should always consult a professional coach as we all bring our own idolect (our individual voice) to the work.

How to Start

FOCUS OF THE SOUND or PLACEMENT.

This aspect of accents is sometimes called the “point of placement” or “point of tension.” Another nice term I’m hearing a lot recently is “oral posture.” This is a vital part of accents for performance, but it is also a source of a lot of confusion for people because it is the most subjective element of accents. Why? Because we all don’t think we have one. So how I would describe my accent as opposed to your accent (if it is different to mine) will be informed by my accent’s placement. How you would describe my accent as opposed to your accent would be informed by your own accent’s placement. So, we need to come to an understanding of what this concept is. How it works, and how it can benefit us.

Try this: make a sound, any sound. It could be an AHH, an OOH, an EEE. Then speak a piece of text. Read these words aloud if you like. Imagine that your voice, while you are making these sounds and speaking these words, is a ball of red, vibrating warmth. Where in or around your mouth is that ball sitting, or focused? There are no right or wrong answers – this is subjective remember? Where do you feel that ball is concentrated?

The next layer of that could be asking yourself – is the shape a ball? Or is it a cone? A cylinder? Is it a tube which curves upwards or downwards or outwards? In other words, the way we speak feels natural to us, hence we’re more likely to think of its features as “neutral” or “central” or “free.” That’s why I refer to it as the focus of the sound, because while we all think we don’t have an accent, what this practice is intended to do is bring your voice into another place, to help you find your voice in the accent. So while it is the most nebulous and subjective thing in accents for performance, it is the most useful tool to help us to discover our voice in a different way. And while it is subjective, we can make some generalisations, which may or may not apply depending on your home base.

So, as an Australian speaker, my accent is focused in the middle of my mouth. But if it was a ball, that ball would be halfway between the dome of my hard palate and my nasal cavity – this is because in my accent the jaw tends to be quite closed. I might also, upon examination feel that the space is not so much like a ball, but like a wide flat disc, and thus that the “direction” of my accent is outwards to the sides rather than directly forward.

Now that is my experience of my accent. It’s crucial to develop a sense of this for yourself because this is your “home base” or your comfort zone. To effectively realise an accent, you need to be able to move outside of your comfort zone!

The Standard American accent is conceived of by most non-speakers as being focused in the back of the throat – the pharynx. This is the “engine” I mention below with the K-breath. The sound is focused here but arrives on the lips and teeth and tongue-tip, which are quite active (in my accent the lips are quite inactive). The jaw is also free and open (compared to many other dialects).

The image I often use for my students is to imagine you are talking around a baseball in the back of your mouth. Alternatively, picture two silver quarters between your back molars.

LOOSEN THE JAW

As humans, we tend to hold a lot of our anxiety and worry in our jaw. Some dialects also employ a close or tight jaw to realise their sound. For the Standard American accent we need to loosen the jaw so that we are free to experience a new space, and the sounds we make have space in which to resonate.

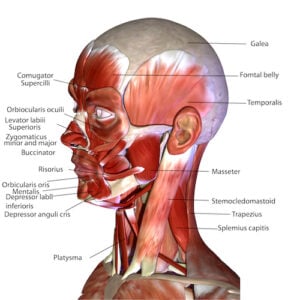

Start by massaging the jaw joint and muscles. There are a few primary muscles involved but the most important to start with are the masseter and the temporalis.

Masseter: Using the thumbs, massage this strong muscle on a point down and forward from your ears. These directions are approximate as we are all shaped slightly differently, but you are looking for the points at which when you press you feel the muscle i.e. not the cheekbones and not the soft tissue of the cheeks (see diagram). Press gently on those muscles and then (also gently) massage them in small circular movements. At the same time, let the jaw open and loosen, and breathe. Keep breathing and focus on freedom, release, and ease.

Temporalis: This muscle is like a fan that extends upwards across the sides of your skull from the jaw. When we clench our jaw, our temples tend to bulge a little – this is part of the action of the temporalis. Using the palms of your hands, massage this area that bulges – or just a little back from it, usually past the hairline. Gently press and gently massage this point – you will know when you’ve found it. Again, make sure the lips are unsealed and you are breathing, while experiencing freedom, release, and ease.

There are lots of other exercises to loosen the jaw like yawning, or stretching the jaw slowly down and up with your hands. Any of these or similar exercises will help open up the space you need.

OPEN PHARYNGEAL SPACE

The pharynx is the back of our throat. The space between the back of our tongue and the soft palate or velum is the gateway to our pharynx. The first thing to do is breath in but place a soft K sound at the beginning of your inbreath – it may sound a bit like a whispered “KAAA” – but should be open and free of tension. Think about a free open in-breath, a bit like when your are pleasantly surprised by something, just with a K at the beginning of it.

Next, breathe out with a soft K at the start. Again, it should sound like a whispered “KAAA” but open and free – imagine you are fogging up a mirror or your glasses if you wear them.

Do this a few more times – breathing in and out on that K, feeling the back of the tongue and the soft palate coming together, and then springing apart. The more you can freely spring them apart, feeling the breath on the back of the throat (but free and open not cold and dry or tense), the more space you will be creating for what I call the “engine” of the Standard American accent.

Next on an outbreath add sound: YOOOOOO. Breath in on that K again, then out on: YAAAHHH. Breathe in on the K, then: YEEEEEE.

Then immediately and in your own natural accent (preferably a broad or exaggerated form thereof) say YOOO, YAAH, YEEE… Now try contrasting each sound individually – a YOO with the open space, then a YOO with your natural space, then the same for the YAH and the YEE.

What you should hopefully feel in your mouth is the sensation a bit like a rubber band having been stretched in one direction for the open YOO YAH YEE, and then of that rubber band releasing or slackening for your natural YOO YAH YEE. The sensation of the open, stretched place is the “placement” of this accent. It is a key to the oral posture.

GET TO KNOW YOUR R’s.

There are more types of R than you might think. Approximant, tapped, trilled, fricative, uvular, and that’s ignoring voiced and voiceless variations! I’ll be writing a whole article on rhoticity and discovering your R and other R’s, but for the Standard American accent we just need to focus on one type – the approximant.

I like to describe the feeling of this R by imagining that your tongue is a turtle’s head. To make the R we’re after, the turtle pulls its head back into its shell (the tongue root retracts), then it looks up slightly (the tongue tip gently lifts). A lot of time is spent by other accent coaches on the nature and quality of the American R. My focus (at least initially) is on making sure you can feel that R position and know it intimately, so that you can know when it is not happening in the right places, or is happening in the wrong places.

The Standard American accent is what is called RHOTIC. This means that they pronounce the letter “r” every single time it is in the spelling, and never when it’s not in the spelling. If your natural accent is rhotic already this will present fewer problems for you – aside from making sure you are using the correct variety of R! However if your natural accent is non- rhotic, which means you only pronounce the letter “r” in specific circumstances, then you will need to pay particular attention to this sound. Some examples of Rhotic dialects include Standard American, Canadian, Irish, Scottish, Cornish, and even specific parts of South Island New Zealand. Some examples of Non-Rhotic dialects include Received Pronunciation, most Northern English dialects, New York, classic Southern American, Australian, South African.

Note that for many people for whom English is their second language, rhoticity is a common feature (often in learning languages we are guided by the spelling or orthography), but the type of R used will often be very different, and it depends very much on whether you have learned American English, or British English. If English is your second language you should definitely seek the guidance of a dialect coach who specialises in what is usually called foreign accent reduction or FAR.

CHOOSE YOUR WORDS.

The rhythm of accents is another “musical” feature which is key to their authenticity. The Standard American accent uses pitch and volume to shape sense and make thoughts clear. For a contrast, Received Pronunciation largely relies on pitch to convey this layer of meaning.

Word emphasis is a big topic (see below on Little R’s) but basically English as a language emphasises the most important words in a sentence, and it’s on those words that the pitch and the emphasis changes. Other languages don’t always do this: many Chinese or African dialects use pitch to change the meaning of words, while in French syllabic emphasis is largely irrelevant to meaning.

In English the pitch and stress changes on the most important words in the sentence or thought. When it comes to dialect, it’s a matter of how far the pitch changes and where it goes when it does. In Received Pronunciation as mentioned before, the pitch moves a lot, and usually doesn’t depend too much on emphasis or stress.

In Standard American the pitch generally moves very slightly – in tones or semi-tones – and is always accompanied by a decisive emphasis on the word or syllable. Thoughts also tend to end on a downward inflection (not always, but it is a tendency).

What not to do

Don’t go for the “twang.”

Many people attempting the American accent think of “the American twang” but really, what does this mean? “Twang” is an undefined, non-specific mood. My first-year acting teacher taught me that “mood” was DOOM spelled backwards. So don’t go for something vague and undefined. “Twang” tends to lead to nasality, which while it isn’t necessarily a bad thing for American accents, is not something you should reach for or aspire to. Finding your voice in the accent as I have already said is key. My go to for this is always warmth. Focus on warmth in your voice as an attitude and as an approach. This invariably brings you to a more authentic place and back into yourself.

Focus on the R too much.

Don’t get me wrong, the R, or the rhoticity, is vitally important to achieving an authentic American accent. I describe it as one of the key architectural features – it’s like the foundations and the supporting beams – if it’s not there the whole accent falls down. However, the R is a sound which most of us will find easy to achieve and realise. It does not need to be OVER-pronounced. This is why I usually focus less on how the R is made than on where it is used. The most common mistake I observe with the R is over-pronouncing it, that is using too much tension. Say that R again – feel the turtle pulls its head back and slightly looking up. How far up is the turtle looking? Keep the R going as you curl the tongue-tip further up, then further, then all the way back so it’s what we call retroflex. Do you feel how the “quality” of the R changes depending on how far the tongue-tip curls up or back? It also depends on how much the tongue root is pulling back as well, but hopefully this shows you how the approximant R can vary.

So long as you know what the basic approximant R feels like, you will be able to notice where you are doing it and where you are not. The R is no different to the M or the T or the SH. They are all phonemes (sounds) which we are all capable of making as human beings. It is simply a case of the order in which we place them, the oral posture that communicates them, and how we understand them together. That is language and that is dialect. Discover the sound, even if it is new to you, and then trust it.

Common mistakes and how to overcome them

Little R’s

Syllables in English are either stressed or unstressed – emphasised or not, weighted or not. In other languages syllabic emphasis is irrelevant, and in others there are strict rules for syllabic emphasis. What syllable to stress is important to be aware of in English because syllabic emphasis can change the meaning of the word you are using. For example:

recount – to count again

recount – to relate or tell a story

resource – a noun, a source of supply

resource – a verb, to allocate resources

produce – a noun, what has been produced

produce – a verb, to bring forth

attribute – a noun, a quality of something

attribute – a verb, to ascribe a quality to something

Furthermore the word that you stress can change the meaning of the sentence. For example:

She is happy – as opposed to some other emotional state

She is happy. – confirmation or affirmation, as opposed to some other emotional state, she is not sad.

She is happy. – as opposed to someone else.

How does this relate to rhoticity? Well if you are a non-rhotic speaker then one of your main tasks is to ADD a sound in to your speech in places you are not used to adding it. So when it comes to the R, the rule, as we have said, is simple – R is pronounced every time it is in the spelling, and never when it’s not – but because of the way English syllables and word-stress works we have two types of R: stressed and unstressed, which I sometimes call Big R’s and Little R’s.

A word like “smarter” contains a big R then a little R because the first syllable is stressed and the second is unstressed. It’s those unstressed, Little R’s that are so easy for we non-rhotic speakers to forget. In other words we are more likely to make the mistake of saying:

“SMAR-duh” than the mistake of saying “SMAH-der.”

Long story short, every R is important, hence becoming familiar with what R feels like because it always needs to be there, even if it is unstressed. Your R should feel relaxed and natural as opposed to hard and stressed. It is the syllable that is stressed, not the R.

“Been”

For Americans this word is always pronounced with a short vowel rather than a long vowel. In other words:

“bin” not “been”

How’ve you been?

I’ve been good.

It’s been hot lately.

How long have you been here?

If, to your ear, it occasionally sounds like “ben” that’s because the short vowel involved in “bin” is more open for that person.

“Our” “Your” We’re” “For” and “Or”

These words can vary in their realisations across dialects of English. They are also usually unstressed words in most sentences. But whether stressed or unstressed, when attempting the General American accent the following guidelines should make things easier, at least until you’re more confident.

“our” : Think of this word as “ARR” (i.e. not “ow-r”); “OW-er” is usually “hour”: Our journey took hours.

“your”/” you’re” : Think of these like “yrr” or “yer” (i.e. not “YAWR”) You’re thinking of the days of yore.

“we’re” : Think of this word as “wrr” or “wur” (i.e. not “WEE-uhr”) We’re going to the weir.

“for” : Think of this work like “frr” or “fur” (i.e. not “FORR” or “FAWr”) Four for me, and five for you. Foresight for forethought.

“or” : Think of this word like “er” or just “r” by itself (i.e. not “ORR” or “AWr”) This or that? Mine or yours?

A great trick is to join the little or unstressed word on to the previous word to create a nonsense word that when you run the thought together it becomes clear.

They liked our house (they laiktar house)

We heard your speech (we heardyer speech)

Cold or hot? (colder hot)

Get some for me (get sumfer me)

Time to talk

I hope this introductory article has given you some more specific things to think about for when you speak in an American accent, but also when you listen to an American accent. Take everything I’ve just talked about and use it the next time you watch an American film or television show. What do you notice about that actor’s R’s? How about that actor’s oral posture? What about that actor’s pitch and word emphasis? How are they different to you? Repeat these things as you hear them, feel them in your mouth and your body. Feel their unfamiliarity, and find a place where they can feel familiar (building your voice in the accent)

Now be bold, pick up a random piece of text and start to read it in your best American accent. Do not be afraid to fail. Discover words you’re unsure of. Start to try to discover what it is about those words which are tripping you up. Is it the spelling? The syllabic emphasis? Is there an R involved? Could it be to do with the words on either side of it?

BE CURIOUS.

I’ll end with something I also often tell my students: the safest place to practice your accent is in public.

Yes, truly. No one is going to question what you present yourself as – unless of course they’ve met you before or know you well!

Be brave and bold, and experience. And if you need to, contact a professional coach. We’re here to help!

Leave a Reply