How to Cut Down a Monologue or Scene

American author William Faulkner is generally thought to have coined the phrase “kill your darlings”: a now-popular piece of wisdom handed to writers about cutting the parts of their work they might love but don’t really need. It sounds like brutal advice, but it’s always for the betterment of the larger work; and these days, in the age of the auto-save, it’s not like you can’t undo your murder with a few, choice keystrokes.

As an actor, it’s important to learn how to cut down a monologue or scene. You might want to make the perfect script work for an audition, or perhaps shave crucial seconds off a potential showreel piece. When making cuts, always ensure the intention of the scene is still apparent, the character’s voice is clear and that you’ve not lost the ‘spirit’ of the writing.

Sounds easy enough, right? It’s not like their your darlings that you’re killing… But actors come to me with questions on cutting down scripts all the time; there’s always a genuine fear that you might cut the ‘wrong’ bit or it will lose what they loved about it in the first place. So this article will give you a few pointers, and even take you through a couple of examples.

Why Cut Down a Monologue or Scene?

In short? Length. The length of a monologue or scene is always going to be an enemy of the actor, especially in an audition context. They battle the schedule, or short attention span of potential agents and collaborators, or the casting agent with another 139 people to look at (who all, scarily, look and sound exactly like you.)

Beyond the purely logical aspects, a longer scene often robs the material of its punch when not contextualised by the larger story. What might feel like a breathless, engaging monologue within a three hour film might suddenly drag without the action around it.

And this is especially important within the context of your showreel (or demo reel.) Showreel scenes need to get to the point, showcase you (not your scene partner) and end someplace quick and coherent. Just like acting for a self-tape, showreel scenes are sort of like their very own genre.

What to Cut:

Cutting material down from a monologue or scene is always a subjective process. There is no right or wrong way to do it, but there are some considerations you can take into account to make the process easier. We’ll talk over a few key basics below:

- Repetition. Do characters have a few quippy backs-and-forths before the scene gets going? There might be a repeated catchphrase, or somebody says something over and over to their scene partner for dramatic or comic effect. Banter is always fun … but do you need it?

- Padding. Can you identify any unnecessary lines/exchanges in between bigger moments? These are some of the most expendable parts of a scene, and you’ll find them peppered throughout even the best-written material.

- Long speeches. Examine chunks of text in the scene. Do they add to the story? Or do they rob the scene of its urgency? You might be able to get away with one speech that features you, but this needs to be earned by the larger drama of the scene’s context. Can you get away with cutting some of the speech and not all of it?

- Backstory! We will assume you’ve gone through your script analysis process, and you have a clear idea of your character’s journey, objective and the given circumstances of the larger story. But if you’re making cuts, consider material that references other scenes. Remember that your audience isn’t the expert on this scene you are. Try without and see if it still works.

- A weak beginning/ending. Do your characters ask each other how their morning was before they start to discuss a planned robbery? Does one character flare up at the other and then spend a minute comforting post-climax? Don’t settle for weak or meandering beginnings and exits. They might feel natural … but that’s not the ball game right now. Start the scene where it gets good, and get out after the good bit!

- Action. Consider making cuts to physical actions characters perform. Toasting drinks, lighting cigarettes, standing up and sitting down. All of these actions can waste valuable time

Final note:

Above all, keep the scene ‘present’. It needs to speak to its own here and now, and not set something else up or pay off in a later reveal—something that we’re never going to see. Let it stand on its own, and focus on the individual wants and objectives of the characters. That is where the drama of the moment comes from.

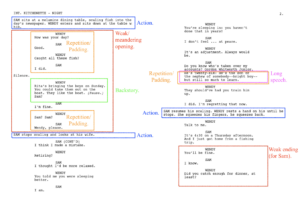

Case Study: “Wendy & Sam”

Let’s look at a scene for some examples of the above cutting suggestions. We’ll upload the original, untouched version, so you can have a go at making your own cuts:

Note that if you followed every direction in the above script, there’d probably only be a few lines left! So do exercise some restraint. And, as soon as you can, read through the scene with a fellow actor and for an audience unaware of the original material. You may even find yourself putting bits back in.

When can I Add to a Monologue or Scene?

Ooft. This is a tricky one. Unless it’s an audition side you’ve been sent—in which case the answer is “Add as much as you don’t want to get the job!”—there isn’t technically anything wrong with adding a word here or there. But I’d strongly recommend against it. ’cause where does it end?

There are plenty of reasons you might add something to a scene: to speak to the wider context, to a character quirk the audience might find entertaining. It might have something to do with an earlier scene that gives this monologue dramatic irony. Or maybe you think the character comes off in a bad light in this particular moment and you want to take something from later in the story when they become more sympathetic.

However, none of this is what the writer intended. At no point, in all their years of working on this story, did they ever think your addition needed to be there. If it did, they’d have written it already. This is why additions are bad news. Cutting a script might feel like you’re disrespecting the writer, but at least you’re not diluting their words with your own.

Making Changes

Making changes to a script isn’t quite as blasphemous as adding things. That said, it’s still important to be careful and to do so with good reason. Changing the pronouns of a character to suit you, and perhaps a name or two in the same vein, isn’t much of a problem. In fact, many of the scenes on StageMilk’s very own practice scripts for actors and practice monologues for actors are gender neutral to circumvent this need entirely.

However, changing a character’s job description, or the way they they communicate in the scene, can modify things greatly. Script analysis tells us that every word on the page, every punctuation mark, is worth interrogation. So chances are, if you’re changing things, you’re as good as weakening the script—even with the best intentions.

Ultimately, the situation dictates. If a few small modifications are going to help you better connect with the material, go for it. But the best piece of advice is to avoid adding to the material: make what’s already there work. As an actor, it’s sort of your entire job.

Can I Write my own Monologue or Scene?

Hells yeah you can! If all else fails with your editing efforts—if you’re making more cuts than Sweeney Todd and adding more lines than the original author—writing something original is always an option. We talk about writing for yourself a lot on StageMilk, as we think having a writer’s perspective as an actor is an invaluable skill set. So we’ll leave a few good resources below for you to peruse if you’re thinking of sitting at a typewriter and bleeding:

- How to Write a Vehicle for Yourself

- How to Write a Cabaret

- How to Write a Monologue

- How to Write a Short Film

- How to Write your First Screenplay

- And How to Tell your Friend their Script is Terrible (if you’re feeling brave.)

Conclusion

Let me leave you with this thought: it’s not strictly ‘cutting’ that you’re doing to a script. It’s editing. Any writer will tell you that editing—while tough at the best of times—is no less part of the creative process. Quite often, it’s the time when the piece finally comes together and becomes its best version. So when you go to cut down a monologue or scene, remember to respect the text: respect its ‘spirit’ and meaning. If you do that, you’re sure to keep the good stuff every time.

Good luck!

Leave a Reply