Richard II Monologue Act 4 Scene 1

Richard II is one of my favourite Shakespeare plays. It was one of Shakespeare’s earlier plays, written around 1595, and to many critics, it is too simple and lacks the nuance of his later work. But you know what? I love simple. I think the play is easy to follow, entertaining and has some of Shakespeare’s finest poetry. For an actor exploring a monologue from this play, you are in luck. It is a real gift to the modern actor; it has the lofty poetry Shakespeare is famous for but doesn’t require extensive detective work as the metre is quite formulaic and simplistic. Shakespeare’s earlier plays are generally much easier to unpack, it was only as he matured as a writer his work became more fragmented and complex. The text of Richard II feels very approachable.

The purpose of this page is to help unlock and decipher this monologue from Act 4 Scene 1. My aim is to help an actor bring this piece to life so that Shakespeare’s wonderful text can truly penetrate a modern audience. So let’s begin…

Where are we?

Stella Adler and Uta Hagen would be proud of us! We always need to begin by finding our “where”.

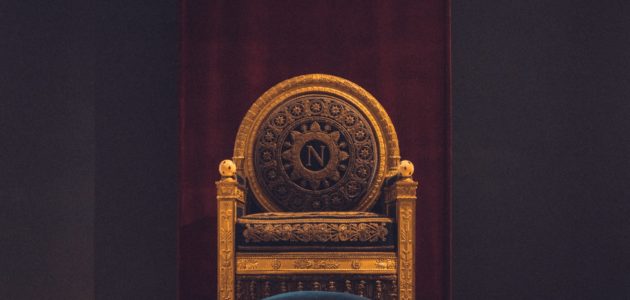

This is so often missed in the monologue work I see as part of StageMilk Drama Club. Knowing where you are and your relationship to that space will bring your work to life. According to the text we are in Westminister Hall. For those of you unfamiliar with London, here is an image of Westminister:

But for what this hall looked like in the late 14th century, one must use their imagination.

The location of the monologue is important because we all have a relationship to place. For one, Richard is the king, and so this is a place he is familiar with and in this environment, he is normally seen as a high-status figure. It is also a very official and formal space, so that would affect how you interact with the surroundings.

Who am I talking to?

This monologue is specifically aimed at Bolingbroke, Richard’s cousin, who is imminently about to take his crown and become king. We also have present Aumerle, Northumberland, Percy, Fitzwater, Surrey, Abbot of Westminster and the Bishop of Carlisle, as well as a few other minor characters. This is important as it is not a private conversation. So as you perform you need to take into account the piercing focus on Bolingbroke, but also the performative element to the collection of lords who are present in the scene.

What is happening, and why…

As we begin to dig into the speech, we reach the murky space of subjectivity. I never like to steer actors too strictly as they are beginning to work on a monologue, but here are a few thoughts…

Shakespeare was an actor, and in that way, he wrote for actors. He guides as well as any playwright, but his work definitely benefits from an actor offering their own creativity.

Richard is a character whose motives are not completely clear. He is upset at being deposed, but not fighting it fervently at this stage. He is also emotional but shows a lot of play and silliness in his work – he is often inclined to some self-depreciation and hyperbole. He is also desperate but seemingly makes no attempt to bargain with Bolingbroke. Part of the tragedy of Richard is that this outcome is completely his own doing. Had he just given Bolingbroke his inheritance, and not been so disrespectful to the lords, he most likely would have carried on in power.

But whatever you think about the character it’s important to make choices. Trust that your interpretation of the character is valid and bring that unique viewpoint to the work.

Richard II Act 4 Scene 1 – Original Text

Ay, no. No, ay; for I must nothing be.

Therefore, no ‘no’, for I resign to thee.

Now mark me how I will undo myself :

I give this heavy weight from off my head,

And this unwieldy sceptre from my hand,

The pride of kingly sway from out my heart;

With mine own tears I wash away my balm,

With mine own hands I give away my crown,

With mine own tongue deny my sacred state,

With mine own breath release all duteous oaths.

All pomp and majesty I do forswear;

My manors, rents, revenues I forgo;

My acts, decrees and statutes I deny.

God pardon all oaths that are broke to me;

God keep all vows unbroke are made to thee.

Make me, that nothing have, with nothing grieved,

And thou with all pleased that hast all achieved.

Long mayst thou live in Richard’s seat to sit,

And soon lie Richard in an earthy pit!

‘God save King Henry’, unkinged Richard says,

‘And send him many years of sunshine days!’ –

What more remains?

Unfamiliar Words

Ay: Yes

Resign: voluntarily give up my crown

Mark: pay attention

Thee: you

Sceptre: an ornamented staff carried by Kings on ceremonial occasions as a symbol of sovereignty/power.

Forswear: renounce

Sway: power

Balm: fragrant oil used for ceremonies, usually placed on a king when they are being anointed

Release: give up

Decree: an official order that has the backing of the law

Statues: a written law that has been approved by a government

Forgo: give up

Dutious: dutiful, obedient

Pomp: grandeur, ceremony

Earthly pit: grave

Unkinged: deposed

Full Modern Translation of Richard II Act 4 Scene 1

Yes, no. No, yes; for I am destined to be nothing.

Therefore, no, no, I will give up my crown to you.

Now pay attention to how I will ruin my legacy

I take this heavy crown off my head

And take this difficult to control sceptre from my hand (unwieldy is a metaphor for the difficulty of being a king)

The pride you get from being king I give to you

With my tears I wash away the royal balm that first anointed me as a king

With my own hands, I willingly hand over my crown

With my words, I am denying my god-given right

With my own words, I let go of all dutiful oaths

All of the ceremony and majesty of being king, I renounce

My many houses and income streams I give up

The laws and orders I have enacted I no longer enforce

God I ask you to pardon the promises that will be broken to me now

And god please keep all promises unbroken to Bolingbroke (potential for sarcasm, as do you really wish him well?)

Allow me, that now has nothing, to not be saddened by anything

And please keep you Bolingbroke happy and content with all you have now achieved

Long may you like on the throne that was meant for me

And hopefully soon will I be lying in my grave

“God save King Henry,” now-deposed Richard says

“And send him many years of happy days”

What else is left?

Professional version:

Conclusion – Final Tips for playing Richard II

I have already touched on a few of the qualities of Richard, but let’s investigate a little further.

The objective truth is that Richard is a terrible king. He surrounds himself by flatters and empties the coffers of the country for his own benefit. He is disrespectful and clearly indecisive in important decision making, which is never a good trait for a king. But once his downfall becomes inevitable, we feel an enormous amount of pity for him. As his crown begins to slip away, we increasingly see his humanity. This pathos and genuine authenticity connect with us as the audience, and we are left torn. It is a very contemporary play in this way, as there is no clear hero and villain.

When building this character the central investigation is exploring Richard’s motives. What drives him? What does he want? And once his downfall is inevitable, as seen clearly in this monologue, what does he want? Why does he not just hand over the crown and go and hideaway in a castle? A character like Bolingbroke is simple. He was grieved, saw an opportunity to become king, and took the crown. Richard is far more complex. But remember in the complexity comes the acting gold. It is Richard’s flaws, his arrogance, his fragility, his impetuousness, that make for some of the greatest speeches in all of Shakespeare. Bolingbroke has no lyrical passages, he hates poetry and imagination as he says in Act 1 scene 3:

O, who can hold a fire in his hand

By thinking on the frosty Caucasus?

Or cloy the hungry edge of appetite

By bare imagination of a feast?

This makes Bolingbroke a simple, straightforward character. Richard is the opposite. He lives in his imagination and loves language, as his power erodes he must find his inward power through words. The one thing they can’t take from him.

He really should have been a poet, not a king, and that gives you so much scope to explore. It seems that only when he falls from the heights of being king that he really come to terms with who he is. As the facade falls away, there is some redemption to be found. And let’s be honest he was made king of England at age 10, was he really ever going to be a stable king?

Conclusion

Have an amazing time working on this piece. Remember there are other great Richard II monologues as well, if you love the character, but aren’t convinced by this particular speech. If you need some help working on this piece, or any audition monologues, I am always here. We have a private group where you can send in monologues and get feedback from some of the best actors, acting teachers and voice teachers in the industry. If you are keen to work with StageMilk one on one and get some extra help check out our online scene club.

Leave a Reply